The Silk Road

You have probably all heard of the Silk Road. It pertains to a 5000 mile network of trading routes across Eurasia from around 115 BC to the 1450s AD. The image of one caravan of camels moving goods all the way from China to Rome isn’t quite accurate however. Instead, caravans would operate on small segments of the route, with items being traded in towns and then continuing with a new caravan along the next segment. As the name of the Silk Road suggests, one of the main trade products was silk, with it moving from China over to Europe. Another big commodity, going in the reverse direction from Central Asia to China, were horses. This was the reason the Silk Road began in fact. The soil in China lacked Selenium, which meant Chinese horses lacked muscular strength and had reduced growth. The Chinese wanted the superior horses that existed on the Steppes of Central Asia, bred by nomads. The nomads wanted silk and grain, and thus the trading began. Other products were introduced as time went on and trade routes expanded: spices, tea, honey, wine, gold, dyes, perfumes and porcelain. It wasn’t just products that moved along the Silk Road, it provided an unprecedented diffusion of ideas, religions (especially Buddhism), philosophies and scientific discoveries. It was the very beginning of globalisation. Not all that was transported was positive, with some scholars believing that the Great Plague was spread to Europe from Asia along the Silk Road. Its impacts on world history can’t be overstated in my opinion!

The Silk Road came to an end with the rise of the Ottoman Empire, which severed trade between East and West. Sea routes began to be used instead of going overland, and this led to the age of exploration with Europeans discovering the Americas and beyond. There is now a ‘New Silk Road’, a name given to several large infrastructure projects hoping to expand transportation along the historic trade route. An example is the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ funded by China, and I’ve had the pleasure of using some of the new roads myself when in Turkey.

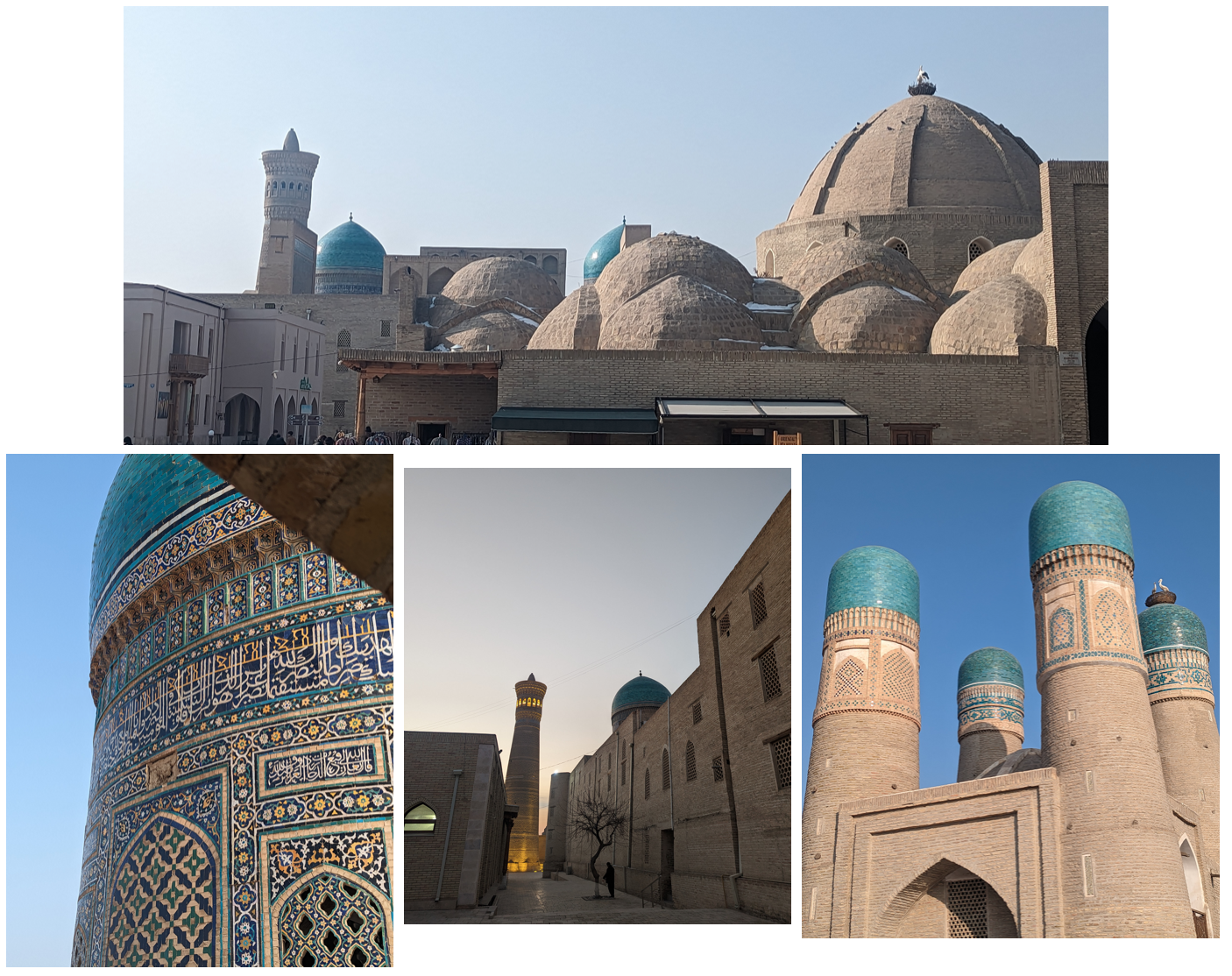

Along the Silk Road several cities were established, as an oasis to the caravans. These were places for the caravan to rest, for the merchants to trade, and for the travellers to socialise. This is where the exchange of ideas, philosophy and religion happened. These towns all had caravanserai which were the ancient hostel in a way. Often a courtyard shape, with the animals being kept on the ground floor, with rooms for the travellers on a second floor. The first caravanserai I encountered on my trip was in Sarajevo, Bosnia. Since then I’ve seen countless others, especially in Turkey. The caravanserai are often the only hint at the city’s Silk Road history. The cities have evolved into something quite different, and have a life of their own now. When you enter the Silk Road cities of Uzbekistan this period of their history is all you can comprehend. They remain frozen as safe havens in the desert. Maybe it’s because I’m currently reading a book set along the Silk Road (thanks for sending it to me Alex!) but as I roamed the deserted streets of Khiva at sunrise I felt like I was experiencing it as a traveller who had spent weeks in the desert, overjoyed to be back in civilisation, rather than a backpacker who had spent 22 hours on a train! I don’t know why hype of these cities hasn’t reached England, but it will soon I’m sure. They all have similar architecture, namely brown mud walls with the flash of blue ceramics in every shade imaginable, in a frequency that gives the city colour whilst still being rare enough to feel like you’ve stumbled upon a treasure. They all have multiple mosques, minarets, markets and madrasahs (old Islamic schools). They all have a main square called the Registan. Whilst these features derive from the Islamic history of the cities, their grandeur and importance comes from its place on the Silk Road. The wealth that the trade brought and throngs of people passing through meant it was both possible and necessary to build such huge structures. The history of these places is one of the most palpable I’ve ever experienced - on the same level as walking around the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, or Pompeii in Italy. But unlike these places, they feel more alive. Real people still live in the Old Town, new merchants selling handmade fabric and ceramic goods fill the holes of the ancient bazaars and trading domes.

My travels

I crossed into Uzbekistan from south Kyrgystan, getting a marshrutka the short distance from Osh to the border. I crossed on foot, experiencing much interest and suspicion over my British passport. I had to wait a while at the Uzbek side, with them appearing to be unsure over whether I needed a visa to enter or not (I did not). As I waited for the guard to return with my passport, the other guard was very curious about my marital status! Once I got through I exchanged my small amount of leftover Kyrgyz som to Uzbek som, being startled by the exchange rate with was 14,000 som to £1! I took my wad of cash and put my head down to march through the battlefield of taxi drivers. They were the most forceful I’d experienced in Central Asia, but I’d done my research and knew there was a public bus which stopped just past the taxi ranks. I rammed myself onto this, standing ladled with my bags for an hour. We arrived into Andijan and from here I was able to get a shared taxi to Ferghana where my taxi driver offloaded me into a damas (a tiny van that I’d already clocked were everywhere in Uzbekistan) which took me to Margilan. The whole journey took about 4.5 hours (including the border crossing) and cost £5.90, which depleted my Uzbek soms. I checked into my hotel and walked into the city centre to do the new country admin of taking out some money and getting a sim card. A problem revealed itself - there was a city wide powercut. No electricity meant no ATMs were working and no wifi was working. This meant I had no money and no internet, also being unable to get a sim card. I was rather stuck! I visited a silk factory whilst I prayed the power would return, risking my life walking around the city as no power also meant no traffic lights. Eventually I saw lights flickering back on in all of the shops, and I raced to join the long line at the ATM. I returned to the hotel with money, a sim card, and a strange sense of accomplishment!

From Margilan I travelled 22 hours by train to Khiva - my first real Silk Road city. The train journey was long but easily spent with blog writing, watching netflix and chatting to the group of old women who spent an hour showing me videos from the wedding they’d been attending and photos of all of their grandchildren. They also gave me an entire loaf (well, circle) of bread?

Khiva

I arrived at sunrise and made the most of this by exploring the old town in the morning light, devoid of any other people. The old town was small, surrounded by a big city wall and completely conserved within, no modern buildings in sight. It felt like walking around a film set, or an open air museum. I learnt that the town has been heavily restored, which is maybe why I didn’t love it quite as much as you’d imagine. It had an air of fakeness to it which subtracted from the historical ambience. It was still pretty cool though. I especially loved the Kalta Minor Minaret, an unfinished tower which was short but charmingly wide, and completely covered in blue mosaics. Khiva was the city where I felt most encapsulated in the history. The little streets with small doorways, shops filled with bright fabrics and ceramics hidden within. Items so beautiful that they were too much for even me to pass up on, and I purchased a beautiful, and reversible, silk and cotton jacket. I bought the ‘VIP’ ticket (actually, it was the only type of ticket so really it should just be called standard) so I could visit the Mausoleum and go up the tall minaret, only to find out neither of these were actually included in the ticket. What was included in the overpriced ticket? No less than 15 of the worst ‘museums’ I have ever visited. Most had no english translations and seemed to house a completely eclectic collection of items (see image of one of these items, a rare one with an english translation). But after shelling out for the stupid ticket I’d be damned if I wasn’t going to visit every last one of them. It became a mission to cross them all off the little map stapled to my ticket and one that left me quite tired by the end. The only two things worth seeing where the Kuhana Ark, where you could climb up a tower for views of the city (but don’t go too near to closing time, as they don’t check if anyone’s on top before closing the door at the bottom…), and the Toshhovli palace. But it was fun to enter into all of the Madrasahs which housed the museums I suppose.

Unexpectedly, I met an english girl (Alice) in the lovely terrace restaurant in Khiva, and it turns out she was doing a similar journey to me (England to Australia overland)! It was wonderful to compare our routes so far, and commiserate on our shared disappointment of not being able to do the ferry crossing from Azerbaijan to Kazakhstan.

Bukhara

Eight hours by train from Khiva lies my next stop. Bukhara’s old town is a bit more spread out, with no big city wall and much wider streets separating the Madrasahs and minarets. Instead of shops buried in small alleys, the merchants occupied large trading domes. The mosques, minarets and Madrasahs were bigger too. It was a bit more lively than quiet Khiva. The Ark Fortress (the old citadel) was off to the side of the old town, and was huge even if 80% of it was still rubble after being bombed by the Red Army in the 1920s. I ventured inside and was told I had to buy a ticket, after my negative experience in Khiva I asked what exactly the ticket included and was told three museums. It was £3 so I decided I would do it. Climbing up to the main area I was disappointed but unsurprised to find that 2 of the museums were locked, and there wasn’t much to see up there at all. Armed with my complaint I returned to the ticket office and was gaslighted by the woman who insisted the museums were open. Eventually I was escorted back up and wow, the museums were locked! A guy came and unlocked them. It turns out he was the manager of the fortress and he ended up giving me a full guided tour, probably feeling like he had to after seeing my very unimpressed expression. When he couldn’t answer my questions on the history of Bukhara he called up the head of the history department, at this point I was feeling very lucky! Both of them then took me to the non-public parts of the fortress which was pretty cool.

Samarkand

A much shorter 2.5 hour train journey took me to Samarkand, my final Silk Road city. Samarkand was the one place I had heard about previously, peering at the impressive photos of the Registan Square on my laptop all those years ago when I started to plan my trip. I arrived in the evening and after dropping my bags at the hostel, decided to go for a run. It had dawned on me that I was planning to do my Himalayan hike in only 6 weeks and I hadn’t done any cardio in months! It also shows just how safe I feel in Uzbekistan, I wouldn’t even feel comfortable going for a run at night in London. I ran down to the Registan Square and got my first look at it, all lit up. It looked a bit smaller than I’d imagined, but was utterly beautiful. I couldn’t believe I was seeing it with my own eyes. The following day I returned in the sun, taking my time to explore each of the three Madrasahs. The first one I entered, Ulugh Beg Madrasah, was my favourite. On entering the courtyard my jaw literally dropped, and I audibly said “wow” to no one but myself. I’ve seen some really beautiful sights over the last 8.5 months, and this is the first one that has actually left me speechless. And I’d spent the last week visiting Silk Road sights. That tells you all you need to know! But I’ll give you a description anyway… Two stories surrounding a courtyard, every inch of wall covered in mosaic tiles in blue, white, yellow, orange and green. I climbed to the second floor, being at eye level with the arches as they were filled with sunlight. The more you looked the more details revealed themselves, and the more it felt like the beauty and history was unravelling for you. The colours and warmth surrounding me in a bubble of mosaic heaven. I took SO many photos! The other two Madrasahs were also beautiful, and I especially liked the tiger details on the front of the Sherdor Madrasah. A part from the Registan Square, which is definitely the crown jewel of the Silk Road, Samarkand has a few Mausoleums and mosques scattered around. One which surprised me in it’s uniqueness was the Shah-i-Zinda complex. This is several Mausoleums in a row, forming a narrow corridor which means your entire perspective is filled with mosaics. Samarkand is a much more modern city than Bukhara or Khiva. When you stepped away from whatever mosque or madrasah you were visiting, you were sucked back into modern day leaving the Silk Road history behind.

I had a few days in Samarkand as I waited for my Tajikistan e-visa to be approved, and I really enjoyed taking the time to savour each of the sights. The sunny weather was also much appreciated. And the company of Alice who caught up with me here! From Samarkand I got an overnight train to Dushanbe, Tajikistan. I’d be returning to Uzbekistan to visit Tashkent which is where I would be heading to my next destination (sadly by flight), but I’ll keep that a surprise for now!

I thought I might get tired of Silk Road cities after visiting three in a row, but I abolutely did not. All three were so different and I’m really not sure which was my favourite. The Registan Square in Samarkand was definitely the highlight, but the overall vibe of Khiva and Bukhara were more special. I’m sorry to say you have to visit all three in my opinion, no shortcuts available here!

Tashkent

My return to Tashkent was brief and uneventful, but I enjoyed going to both a ballet and an opera at the national theatre. Even more so because they only cost £2.20 each! I had some fun changing my leftover Tajik somoni to Uzbek som with a random man at the bazaar. I said goodbye to my pair of jeans that were ripped beyond saving after I’d already sewed them up 3 times. I excitedly waited for my flight to India!

People in Uzbekistan

I had been told by people in Kazakhstan and Kyrgystan that Uzbek people were the nicest and most friendly in Central Asia. This wasn’t my complete experience. I found that I was hassled the most in Uzbekistan, by taxi drivers, by people selling souvenirs, by sellers in bazaars. Probably because people are more used to tourists in the Silk Road cities? On trains, people mostly left me alone rather than striking up conversation and being very friendly. In my experience, Kazakhs remain the most friendly in Central Asia. I did have some very lovely interactions, with one of my guesthouse owners cooking me traditional plov as a ‘gift’. In Samarkand I had groups of teenage girls come up to me on three separate occasions to ask to speak to me - wanting to practice their english, ask me questions and take photos with me. One group even wanted to film an interview with me, asking me about how I’d found Samarkand.