A break from the travel posts for a bit of science.

The highlight fresh produce of my trip so far has undoubtedly been figs. Fig season begins in mid-May so basically when my trip started. As I travelled south I came across more and more of them, with them being a familiar sight at any fruit market and a nice surprise on any fig tree. They had so much more flavour than the ones in England, and I became hooked on them. It was a simple pleasure to eat something in season, and watch it slowly disappear from markets as the season ended. (Thank god for dried figs now!) But what I really love about figs is their biology.

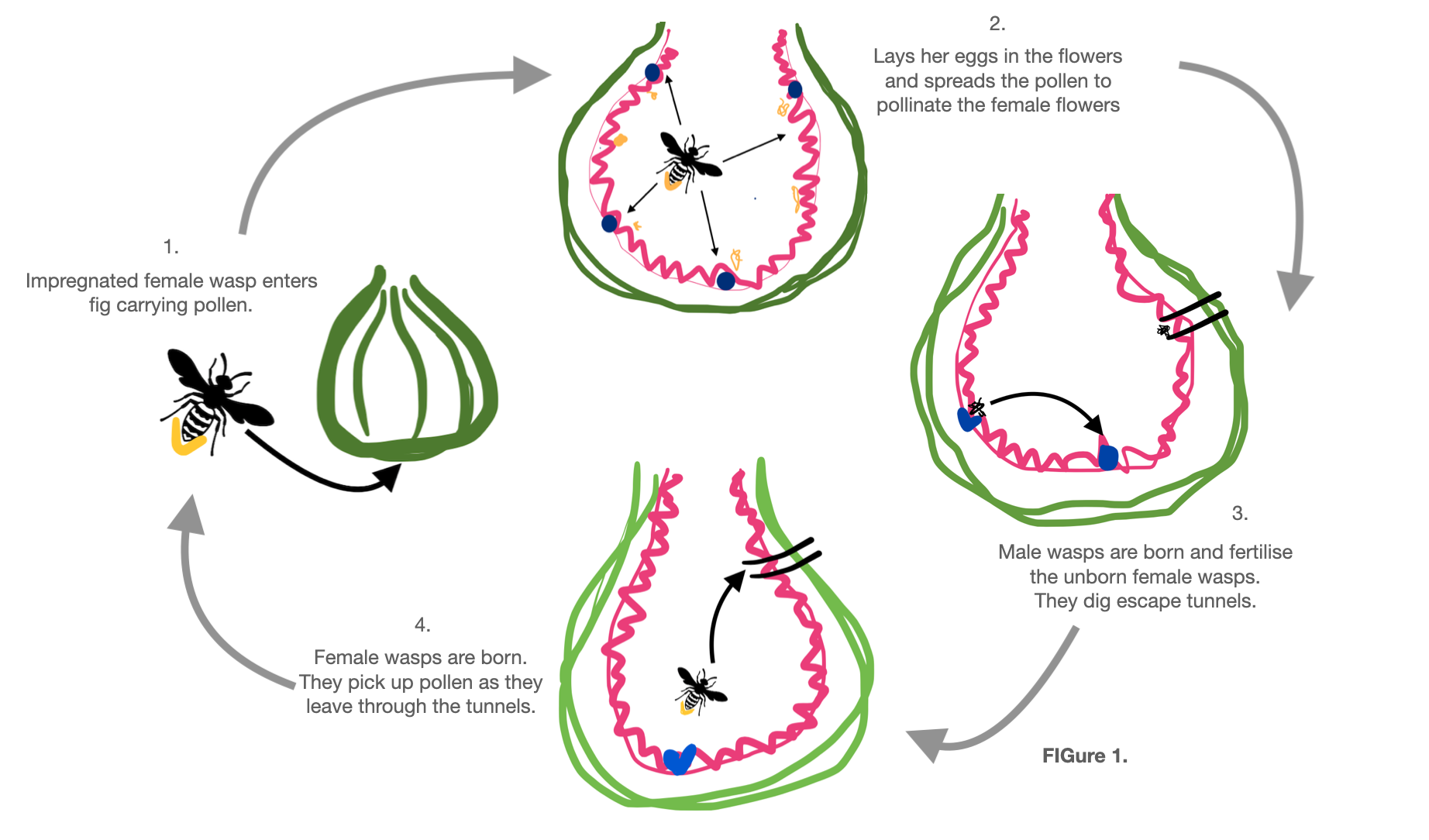

Figs are pollinated by fig wasps, with each of the 850+ species of fig having a specific fig wasp. Figs contain both male and female flowers, which are the little stringy bits inside a fig. This makes a fig a flower not a fruit, interestingly. When a fig is ready to be pollinated it releases an aroma which attracts the corresponding fig wasp species. The female wasp, covered in pollen, crawls into the unripe fig through a small hole in the bottom and lays eggs within some of the flowers before dying inside. As it does this the wasp spreads its pollen around, pollinating the female flowers. The flowers that don’t have eggs inside form seeds. As the fig matures, male wasps emerge from their eggs first and find female wasps which they fertilise while still inside their flowers. The males then dig escape tunnels for the females and die. The females escape through the tunnels, taking pollen from the male flowers. The female flies to another fig tree in search of an unripe fig to lay her eggs in, delivering the pollen to the female flowers inside. And so the cycle continues! The reason I learnt about fig wasps during my degree was because of their use as a model organism for parasitoids, which are small insects that live off of bigger insects (like parasites). But the overall fig and fig wasp cycle is more interesting to me now. It’s a beautiful example of coevolution and a symbiotic relationship, which has existed for 90 million years. The fig cannot survive without the fig wasp, and the fig wasp cannot survive without the fig.

FIGure 1. (see what I did there): A poorly drawn diagram by me showing the life cycle.

But don’t freak out, it’s unlikely you’ll get a mouthful of dead wasps when you eat a fig! Commercially grown figs are often still pollinated by fig wasps but the deceased wasps inside are broken down by enzymes within the fig called ficain and used to provide nutrients to the fig plant. The same is true for wild figs. And some commercially grown figs are self-pollinating so no wasps are involved. But after the millions of years that fig wasps and wasps have spent perfecting their partnership it seems a shame to not involve it in growing figs today. If anyone asks “what’s the point in wasps?” you can now answer “figs”.